As humans, we have some games which combine athletic activities with rationally-based rules and point systems. Thus, while our sports may at a certain level share a basic purpose of promoting teamwork and staying in shape with the games a pride of lions play, our games contain a rational, structured element which is unique to human activities.

Other games, however, are strictly rational games in that they employ some combination of skill and chance, but involve no real physical activity. Among the games of chance (or heavily involving change), some card games go back four hundred years or more. Backgammon and dice games such as craps go back millennia. However other games are strictly games of skill and strategy, and of these there are two particular stand-outs in age and depth of strategy: Chess and Go.

Chess is by far the most familiar to those in Western countries. Originating in India around the 6th century AD, there are clearly recognizable chess variants throughout the Middle East and Far East, including the Japanese game of Shogi. Chess is essentially a fight to annihilate (or at least decapitate) the enemy, and because the pieces can only move in specific ways, there's usually a fairly limited number of reasonable move options at any given point in the game. This both makes the opening absolutely key to the course of the game -- with top chess players memorizing numerous standard opening sequences and the proper counters and variations to them. This limited number of good moves at any given point is one of the things that makes computers so good at chess: when it comes to calculating the likely results of making every possible move, computers usually far exceed human ability.

Chess is by far the most familiar to those in Western countries. Originating in India around the 6th century AD, there are clearly recognizable chess variants throughout the Middle East and Far East, including the Japanese game of Shogi. Chess is essentially a fight to annihilate (or at least decapitate) the enemy, and because the pieces can only move in specific ways, there's usually a fairly limited number of reasonable move options at any given point in the game. This both makes the opening absolutely key to the course of the game -- with top chess players memorizing numerous standard opening sequences and the proper counters and variations to them. This limited number of good moves at any given point is one of the things that makes computers so good at chess: when it comes to calculating the likely results of making every possible move, computers usually far exceed human ability. Go has only become known of in the West in the last hundred years or so, and is still far less well known than chess, however it's history stretches back nearly four thousand years to ancient China. The game is widely popular in China, Korea and Japan, and has a certain (though must less well known) following in America and Europe.

Go has only become known of in the West in the last hundred years or so, and is still far less well known than chess, however it's history stretches back nearly four thousand years to ancient China. The game is widely popular in China, Korea and Japan, and has a certain (though must less well known) following in America and Europe.Go's rules are significantly simpler than chess. It is played on a 19x19 board between players playing black and white stones. Stones are played at the intersections of the lines instead on within the squares. Once the stones are played, they remain on the board without being moved, unless the are captured and removed from the board.

Go is essentially a territory-taking game. The goal is to control the majority of the board when the game play ends. Territory is defined as the number of empty intersections which one controls.

The thing that leads to go's incredible strategic complexity is the concept of "life" around which the entire came centers. A stone or group is "alive" if it has adjacent to it or within it "liberties": empty intersections. Any stone or group with no liberties is "dead" and is removed from the board. A group becomes un-kill-able if it contains sufficient internal liberties that you cannot kill it by surrounding it and then filling it it's liberties, because any enemy stones inside will run out of liberties and be killed before the group is. (The black group in the lower left corner of the board above is alive and cannot be killed.)

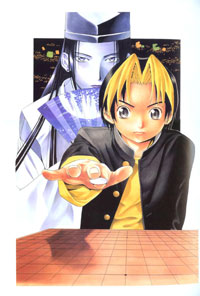

If you want to learn more about go while

generally having a blast, the anime Hikaru No Go (about a 6th grade boy who become acquainted with the ghost of a millenia old go master) is a great way to do it. The series is exciting even for those with no previous acquaintance with the game (read MrsDarwin) and actually teaches a lot of very good go along the way. (Several professional go players consulted on the original manga and the series based on it.)

generally having a blast, the anime Hikaru No Go (about a 6th grade boy who become acquainted with the ghost of a millenia old go master) is a great way to do it. The series is exciting even for those with no previous acquaintance with the game (read MrsDarwin) and actually teaches a lot of very good go along the way. (Several professional go players consulted on the original manga and the series based on it.)Unlike chess, go playing computer programs have only been able to achieve moderate proficiency. No program has beaten even a lowest rank professional player. (Though they can certainly beat me.) The main reason for this is that although the rules themselves are very simple, the number of moves that can be played at any given point is huge, given the 19x19 board. And strategic dominance of the board is less simple to calculate as a goal than checkmating a single piece. Which in turn is one of the fascinating things about the game.

:.

:.

0 comments:

Post a Comment